After the air rebalanced and everyone resumed their preferred angle of repose, Bob turned and said something along the lines of,

“So what would you suggest?”

And suddenly I was doing quick math: harmonic triage in my head.

Stick with E-flat. Something melancholic, yes—but not sappy-sentimental.

No “But Not For Me.” Also, no perk. No jaunty bounce.

I Got Rhythm was out. It might’ve made Ethel Merman famous in Girl Crazy, but that was 1930, and it was way too caffeinated for Bob’s needs.

What he needed was Gershwin with a little fog in it.

And definitely not “A Foggy Day” (in London Town).

All eyes were on me. No pressure.

How about Soon? I offered.

It was a clean solution. A simpler melodic line. A leaner ache.

Built more for inward drift than outward display.

I could hear it with just a guitar, and the grain of a worn voice.

“I’m not familiar with that one,” Bob said.

Well, why don’t I play it for you?

I made my way to the upright piano, off to the left, sat down, and ran through the melody line. Then I played a pared-back rendition, singing quietly:

“Soon…the lonely nights will be ended

Soon…two hearts as one will be blended

I’ve found the happiness I’ve waited for,

The only girl that I was fated for…”

When the song fell quiet, I turned slightly, half over my shoulder, just enough to glimpse their expressions, as if catching the tail end of a thought.

Bob looked… engaged. The kind of gaze that listens even after the sound has stopped. He asked me to play it again.

So I did.

And just like that, he nodded—almost imperceptibly—toward agreement. It might work. That surprised me.

I returned to the sofa and sketched out the chords, the harmonic skeleton; what musicians call a fake sheet.

A semblance of structure.

Truth made portable.

Bob lifted a guitar and began to strum.

Now, I honestly can’t remember if he brought the guitar with him or if it belonged to Ken. I picture him with it in hand already, but that might be the retelling dressing itself. Either way, he strummed through the changes and hit a few walls. The truth is, Dylan wasn’t exactly a guitar virtuoso—not in the Segovia school, anyway. His was more of the Keith Richards sensibility:

Five strings, three chords, two fingers and…a refusal to complicate things.

Which is where Jordan came in. He played guitar too and transposed the song into F to make things a little easier on Bob.

Years later, I was living in México, about as far from Hollywood glamour, celebrities, auditions, or the faintest whiff of the big time as one could drift. I was in Puerto Vallarta, executive chef and general manager of a restaurant where the tide came close enough to stir the silverware. Yes, back in the food game. As my friend Myron Griffin liked to say: “In Hollywood, if you're not buying lunch, you're usually serving it.”

That old chestnut still rang true. Even in Puerto Vallarta. Even with waves licking the sand in my shoes.

And yes, the role brought fulfilment; I trained a group of young cooks, taught them how to fold flavour into form, how a reduction might outlast the day. Taught them food history, too, since none had ever crossed a stage to receive a diploma. I wrote a bilingual cookbook, part narrative poem, part instruction. We were invited to participate in the city’s gourmet festival. We served events and benefits beneath chandeliers and government seals.

Those were, many would tell me, worthy accomplishments. In every respect.

Along the way, quietly, almost between shifts, I released Patria Añorada, later retitled ‘Isla,’ an album of original songs in Spanish. Even performed a few piano recitals in town.

My tenure there culminated in an invitation to cook at the James Beard House. Six of my crew came with me—flown to New York for the event. Three had never set foot on a plane.

They stepped out into Manhattan, necks craned, eyes wide—not at the traffic or the noise, but at the sheer verticality of it all. From Paso Ancho to West 12th Street: a leap so stark it left them blinking upward. They stood in awed silence, not staring at architecture exactly, but absorbing the idea of it. These weren’t just buildings—they were declarations. Form as decree. Scale as verdict. The unfamiliar grammar of height.

It was my proudest moment with that crew.

And yet in all those years in Puerto Vallarta, I carried a long ache.

Unnamed, but persistent.

The unmistakable pangs of exile.

I was far from where I wanted to be.

I was also raising three children. Alone.

Then one afternoon, Tony Bill rang to say a friend of his was in town.

He asked if I’d be available to meet him for dinner.

‘Sure,’ I said.

That evening, Tony’s friend Chuck Plotkin came in by himself. I hadn’t known his name, or his history. We sat, exchanged a few pleasantries. Then the conversation began to unfurl, like a sail catching wind. Turned out he’d been in the record business in Los Angeles. Deep in it. Not just among the notes but helping to shape them. In fact, for years, he’d produced Bob Dylan. Springsteen, too.

I told him the Dylan/Gershwin story, of that night, that quiet gathering, and Bob struggling to find his way into “Soon.”

Chuck listened, his smile a slow arc—measured, weathered, the kind that knows things it will never need to say. He kept nodding, gently, the way someone does who’s stood backstage for half a lifetime and learned what not to explain.

“Yep,” he said. “Sounds like Bob.”

That night unfolded with an easy light; laughter, a shared tempo. A glimmer.

After dinner, he turned to me and said I should join him and his wife on their crossing—sailing across the Pacific.

Tahiti, I think. Or Sydney.

Somewhere imagined and blue.

“Bring the kids,” he said.

Coulda sworn he meant it.

It was tempting.

If only for a minute or two.

It wouldn’t be the last time the Pacific called.

⁂

That night at Ken Lauber’s, I hung around a bit longer, watching Bob run through the song a couple times. After a while, however, I decided my part was done. Others might’ve stayed to bask in the glow, soak up some of the legend.

I chose to leave.

Goodbyes, thank-yous, nods all around, the choreography of parting. Then I headed back to Venice. Back to the restaurant.

When I walked in, service was winding down. A few waiters lingered in the dining room, gathering plates, glassware, voices. The residue of evening.

Guess where I’ve been tonight? I announced, with bemused delight. I couldn’t help myself.

It wasn’t looking to brag, more a kind of wondrous awe I wanted to share. One of those nights you couldn’t have predicted. Couldn’t quite believe. A “What were the odds?” sort of thing.

Even to me, it felt imagined.

I’ve just been with Bob Dylan.

Mind you, this was a crew impervious to starlight.

Seasoned hands who’d served fame nightly,

as matter-of-factly as one might plate a serving of meat loaf,

dressed in red wine jus, nestled beside a cloud of mash and a spoon of braised spinach.

They moved among luminaries as if among furniture;

not indifferent, exactly,

just well-practiced in the art of not staring at the sun.

Still, Dylan was… well, Dylan.

A shadow from the mythos.

The looks I got weren’t disbelief.

Not Are you kidding?

More like: Then why are you here?

Why did you leave?

And it was a fair question,

fair enough to make me rewind the reel,

scrutinise the frames more carefully.

Perhaps it was that old impostor syndrome again,

the shadow at the edge of the stage,

waiting just beyond the applause,

gloves on, blade drawn,

hissing that none of it was ever really mine.

Or maybe I didn’t want to be a hanger-on.

Even for one night.

My part had been played.

The lights had gone low.

⁂

I did cross the Pacific with my kids.

Just a few years later.

But long before that, I stepped away from 72 Market Street—

and from Venice itself—

accepting a job playing piano in Tokyo.

I was drawn partly by the neon riddle of jazz clubs

in a city of paper lanterns,

by the idea of playing in a place where jazz was revered.

And partly by a Japanese beauty

who tilted the compass without trying to.

I took a breath, measured, unpanicked,

and resigned both posts:

72 Market Street, and Maple Drive.

There was also this:

L.A., I had come to see, could keep a person in stasis indefinitely,

not with gravity, but with the memory of momentum.

Hopeful souls, incrementally stalled,

orbiting a silent sun,

drawn by the shimmer of a promise.

Waiting for the call.

The Big Break.

The moment that, for most, never comes.

I had been there eleven years. The dial had nearly stopped ticking. It was time.

Two nights before I left, Dudley invited me to dinner at his beachfront house in Marina del Rey. A gentle farewell. No music playing. On the table, a wine he knew I loved: a bottle of Mouton Rothschild, 1959.

Tony and Helen were there too.

The three of us—Tony, Helen, and I—had been our own small constellation. Not quite Orion’s Belt, but always visible to one another. Something close enough to navigate by.

A different kind of moveable feast: sailing the coast, skimming the hills. Dinners at Helen’s cottage. Impromptu drives to Edwards AFB to watch the shuttle touch earth once more. Brunches that spilled into late afternoons. The curled serenity of Ojai. Morning light in Santa Barbara. A week in Napa, drifting from vineyard to vineyard, guests at the Coppola estate—like figures in a wine-stained dream.

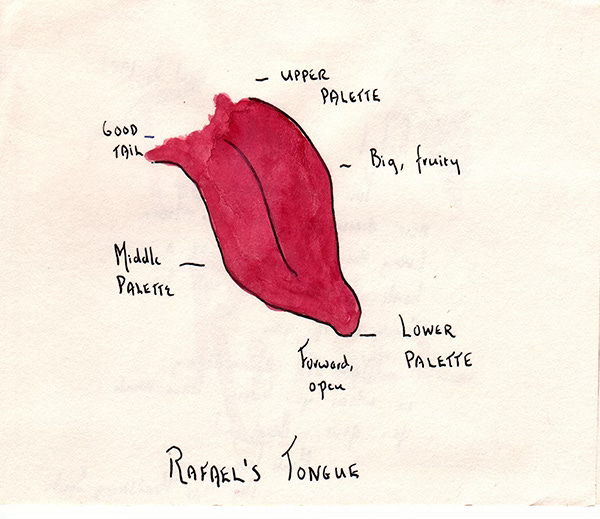

When we returned from Napa, Helen handed me a small hand-painted card she and Courtney had made. A diagram of my tongue—ostensible flavour zones, demarcated. Rafael’s Palate, she called it. A kind of watercolour sonnet. An ode to the week’s slow waltz through wines and laughter, and quiet. A postcard to memory, before it could fade.

We moved constantly, but not aimlessly. The calendar didn’t matter, only the occasions—the ones we made into occasions—the weather, the wine.

There were spas in downtown Los Angeles, where we sat in steamy silence and then giggled over Chinese food. Trips in small airplanes to Santa Fe. Shorter outings to JPL when some gleaming machine in space hummed open the future, and we stood still in its shadow.

It was a rich life.

And I was casting it into the sea.

Tossing it overboard for something unknown.

Not for the first time.

And not for the last.

So I left again. New chapter. Different continent.

I spent nearly two years playing in Roppongi. Picked up a fair bit of acting work; TVCs, the occasional print modelling job. Learned Japanese. Became, to my great surprise, a devoted fan of Sumo wrestling and Japanese culture in general.

⁂

Between Japan and Mexico, there had been a pale interlude in Portland, Oregon. I was back working as a chef.

A rinsed season. Days the colour of parchment. Nights that folded inward.

And one morning, I awoke having dreamt that Helen was pregnant.

They had been trying. For some time.

So, I called. She answered.

Helen: it’s Rafi. I just dreamt you were pregnant.

A pause, then, breathlessly:

“Rafi, we just found out yesterday. We haven’t told anyone yet.”

A few years later, in Mexico, I dreamt again,

and this time, the dream had us living in Australia.

The feeling stayed with me long after waking, gnawed at me all throughout the day, like steamy breath on the glass pane between this world and another.

Pay attention, I thought.

The world sometimes whispers through its sleeve.

So, I called my old friend David Moor, in Sydney. He’d been extending an invitation for years, with the patience of the tide waiting for the moon. That August, I left the kids with my sister in Texas. Visited Australia. I needed to see if that dream had a pulse.

And one year later—give or take—we moved to Sydney. The children and I.

To start a business with someone David had introduced me to on that earlier trip.

But as things turned out, the business was never the point. It was just the decoy the real invitation travelled in.

Roughly six months in, my then partner’s wife—let’s call her Jennie—called one morning.

“Raf,” she said, “I was talking to Belinda last night and she has a friend… Well anyway, would you be interested in meeting someone?”

Yes. She was trying to set me up.

The wild part: that very morning I had dreamt I was introduced to someone.

I told her so.

She laughed and asked me to describe the woman.

I did.

“Well,” she said, “Laura doesn’t quite match that. But do you still want to meet her?”

I said ‘Yes. Of course.’

We met the very next day.

Three weeks later, for my birthday, Laura invited the kids and I to her cottage in Palm Beach.

Afternoon tea, strawberries, puff pastry and cream beneath gauzy light.

The moment I stepped inside, something shifted.

The air, the tempo, the particular quiet of the place.

It was so much like Helen’s cottage.

Tilted, softened, reimagined—but unmistakably, that same vibration.

The curation. The textures. The lived-in warmth. The familiar stacks of half-read New Yorkers.

That sense of legato, of time not halted, but slowed to a lilt.

I must’ve said it half a dozen times:

’This reminds me so much of Helen’s place.’

She smiled.

A few days later, I gifted her a copy of my cookbook, not in search of praise, just sharing what friends had called a good glimpse into my personality.

Opening a window, as it were.

Two weeks passed.

Then Laura called late one night. She said she’d stayed up reading it. This came as a surprise. Shocked, nearly.

“And you know that drawing at the end?” she asked.

At the very end, past the index, I’d slipped in the watercolour—Rafael’s Palate—painted by Helen after our week in Napa. A topography of taste. A tongue as cartographer. I’d dedicated the book to her, to Tony, and to my children. It felt like the right coda. A way to let the silence speak last.

I started in: ‘YES! That one was done by Helen, the Helen I’ve…’

“Stop!” She interrupted.

“I know Helen. We were roommates in New York City twenty years ago.”

She had recognised Helen’s distinctive handwriting.

A sudden, thunderous alignment—lightning-bright, snowfall-quiet. Revelation, distilled.

The world seemed to exhale. The shape of coincidence, briefly visible. Really, what were the odds? But there was more.

Laura’s brother had married the former housemate—and one-time companion—of my friend David. They’d even shared a flat during their med school years. He’d been there, at the wedding. Met the family. A brief crossing. A faint impression.

And at the time of our meeting, Laura was working part-time for a close friend of both David and his wife, Jane. Another thread, idling in the loom.

It became almost absurdly clear: I wasn’t brought to Australia to start a business. I was brought here to meet Laura. In some regards, drawn once more into the undertow of Tony and Helen’s quiet gravity, their presence less apparition than atmosphere. A tide, slow and enduring, still shaping the shoreline of my life, long after the 72 orbit had supposedly ended.

And there was also this: we were living in front of a beach. The Pacific lay within shouting distance—just beyond our balcony. And more mornings than I care to admit, I found myself gazing out, thinking of Tony and Helen, wondering what they might be up to.

Laura and I stayed married eight years, but what remained runs deeper: a bond that outlasted the certificate. Family, still. Family, always.

⁂

The last time I’d seen Dudley was in Portland. 1995.

He’d phoned one morning, out of the blue, to say he was in town, performing with the Oregon Symphony.

Rhapsody in Blue. Of course.

No really. The Rhapsody.

We met at the Heathman Hotel that afternoon.

Martinis at the bar. Two each. Conversation like old cloth, well-worn and softly folded.

At this point, we were old friends, and we shared as much in conversation as we did in silence. The way only old friends can share.

Behind us, women began to appear—one by one, as if summoned by music only they could hear. They drifted toward Dudley in a gentle procession, each carrying the same expression: wonder, reverence, a kind of childlike delight.

They asked for autographs, offered shy compliments, then vanished again, like dancers exiting a stage. He received them all with his usual elegance—unhurried, warm, faintly amused. Flattered, even. Gracious to a fault.

As if fame, too, were just another weather pattern.

⁂

EPILOGUE

Some twenty years later, in Sydney, after the business partnership that unravelled despite the success of the venture, after the financial collapse of 2008, after I’d returned to music and taught piano and harmony for five years, and later still, consulted for a few restaurant groups—I found myself in an office high above the CBD one afternoon when an email arrived:

Hello,

This is a little awkward, but did you ever know a woman named Lynn or spend any time in Georgia or Tennessee, say around 1976? I’m not quite sure what to make of the Ancestry results I received this morning, but I thought I’d follow up and see if you might have any information.

Thank you for your time.

Regards,

Heather.

I remembered the name at once, of course. Lynn. The name, the face, the soft Southern lilt that hovered at the edge of memory, like a perfume recalled but not quite placed. She had been the last petite romance of my Locomotion days in Knoxville, just before Norman and I began to unravel from the other two. Back when the road felt more like a question than a map.

I clicked reply, which took me to her Ancestry page. There, her face looked back at me, features that unmistakably mirrored my mother’s. Almost eerily so. I looked at the predicted relationship:

Parent/Child. Confidence factor: 100%.

The empty room seemed to hold its breath.

Beyond that, there was plenty that resonated: a shared love for music, theatre, languages… She worked as a graphic designer. No surprise, there. Ink and print ran in the family bloodlines. These were all inherited traits, quiet contours of sensibilities that were uncannily familiar. As though remembered before known. As though Heather had been sketched in the margins long before I arrived in Knoxville.

There was also something akin to The Shock of the New—but in reverse.

The shock of the familiar, revealed.

A presence unknown, until it appeared—and then instantly recognised. Whiplash-inducing.

Not a ghost, but the tremors of one:

recognition that upends the scaffolding of our daily reference points,

the ones we rely on for emotional footing, the ones we so often take for granted.

Suddenly, reality as we knew it slips out to sea like receding surf,

leaving us contemplating the foaming sand in stunned silence,

the shore rewritten in its wake.

Still, I hesitated. That uneasy truce between knowing and not—

instinct nodding gently in the dark, intellect fumbling for the key.

I wrote back, hoping to let the sentences breathe,

Yes, I remember Lynn. Yes, she was lovely.

Yes, we shared something, brief, unscripted.

Not love, not quite. A passing constellation.

Still, I held her kindly in the light.

There was nothing to forgive,

no time for resentments.

It had all dissolved before it had time to ossify.

Back then, I moved through places like verses, the stanzas blurred. Towns rolling by like smoke through cornfields, hope rising from Formica counters, sad diner sighs, and faded dreams. A jukebox in the corner, playing its own forgetting.

In those towns, kids leaned against gas pumps like punctuation,

as if posture might impart meaning,

as if staring vacantly were a trade. Old men blinked into the sun,

like they’d seen it all and forgotten most of it,

as if they'd watched the world vanish and return,

twice before noon.

That was before we all left breadcrumbs online,

before we learned to trail ourselves.

Before there was such a thing as an online.

And after her email, I still didn’t know,

not how a father might have entered her life,

nor whether he had entered at all.

So I closed with a small door, left slightly ajar,

the way we sometimes pull notes from the piano

rather than push:

Please tell me more.

Her reply came some thirty minutes later.

Long. Composed with care, each sentence a breath.

She had been raised without a father.

She wasn’t even looking for one.

She just wanted to know if she might be Native American.

Her mother and siblings—blonde, blue-eyed.

She was dark-eyed, dark-haired.

Like my mother. Like my sisters’ daughters.

As if reflection could echo. As if blood remembered.

She hadn’t expected to stumble into me.

A Latino father, of all things.

But Puerto Rican is not a race.

It’s a nationality,

a windward bearing,

a description written in salt.

She wrote of other things. And by the time I reached the halfway point, I knew: She was mine.

I replied without reservation:

If you’re of me, of mine, then I want you in my life.

And I sent her a flurry of photos—her grandparents, her siblings, cousins she would’ve never heard about:

‘This was your grandmother. This was your grandfather. These are your sisters…’

She needed to know.

ASAP.

I wanted to make up for lost time.

Heather had been conceived in Knoxville, born in Georgia—Lynn returning to her own beginnings.

In time, we’ve grown very close. Almost as if I’d raised her.

And along the way, I slowly came to understand something I hadn’t realised I was waiting to learn: That the tide hadn’t only taken things away. It had, all this time, been carrying something back.

A benediction.

⁂

That day, I sat quietly in the middle of the small conference room,

empty of souls, save for my own—

email open, the hum of memory and what might have been

folding over itself like a wave returning.

Not crashing. Just arriving.

Waves of recollections.

I remembered that when I met her mother,

she’d spoken of going west.

Out to California.

A recurring theme in Knoxville at the time.

And now here was Heather,

arriving not with certainty,

but with grace.

A daughter.

A circle closed by unseen compass.

A constellation resolved.

Heather was now living in Southern California.

Near the beach.

The Vast Pacific.

© 2025, Raphael Antonio Nazario, All Rights Reserved.

Photograph of a photograph by Danny Duchovny of Tony Bill and Helen Bartlett. Permission pending.

*From the cookbook, 72 Market St.: Dishes It Out! – A Collection of Recipes and Portraits from a Classic Venice Restaurant, by Roland Gibert with Robert Lia ℗ 1998, © Wave Publishing

Rafael’s music can be found online at YouTube, Soundcloud, on Apple Music: here, here and here (🤷🏻); with more limited selections on Spotify and Bandcamp.

Thank You for reading. I do not offer paid subscriptions via this platform.

Contributions via PayPal, or Patreon—always welcome, with gratitude.

Enter Heather, finally. Hello Heather! Wonderful segment!

There is so much to like about this segment. Agreed, that Soon is much better for Bob Dylan. It is awesome that you have connected with Heather (she’s beautiful)!